By: Nikolas J. Uhlir

Prompting a collective sigh of relief from patent attorneys that represent clients in the software industry, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in Enfish LLC v. Microsoft reversed a lower court’s holding that Enfish’s patent claims – which are directed to software – were invalid for claiming patent-ineligible subject matter under 35 US Code Section 101.

Prompting a collective sigh of relief from patent attorneys that represent clients in the software industry, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in Enfish LLC v. Microsoft reversed a lower court’s holding that Enfish’s patent claims – which are directed to software – were invalid for claiming patent-ineligible subject matter under 35 US Code Section 101.

Enfish is the first Federal Circuit case, after the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Alice Corp. Pty. v. CLS Bank International (2014), to reverse a lower court’s holding that software patent claims are patent-ineligible under Section 101. More important, though, is the insight Enfish provides to patent practitioners and businesses who seek to patent software-based inventions in the United States.

The patents at issue in Enfish are drawn to a logical model for a computer database. Typical logical models create data tables that do not describe how the information therein is arranged in the physical memory of a computer. In contrast, the patents at issue in Enfish relate to a logical model that creates a self-referencing data table that “…includes all data entities… with column definitions provided by rows….” Notably, the Enfish patents assert that the patented logical model enables computers to search and store data more efficiently than prior known logical models.

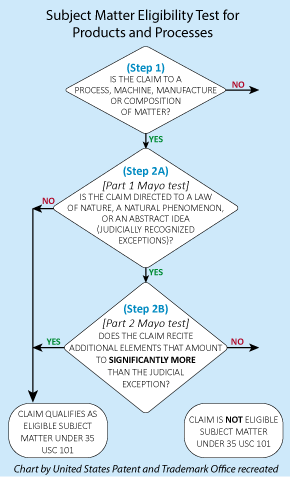

Section 101 provides that a patent may be obtained for “any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof.” Intentionally broad, the language of Section 101 indicates that a wide range of inventions are eligible for patent protection, provided the other statutory requirements for patentability are also met. However, US courts have long since held that laws of nature, natural phenomenon, and abstract ideas are “exceptions” to Section 101 and do not qualify as “patent eligible” subject matter.

In its Alice decision, the Supreme Court applied a two-part test for determining whether a claimed invention was patent eligible under Section 101. Step one of the test requires a court to “…determine whether the claims at issue are directed to a patent-ineligible concept…” such as an abstract idea. If so, step two requires the court to determine whether the claim elements transform the claim into a patent-eligible application, e.g., by providing “substantially more” than a claim to the abstract concept itself.

Unfortunately, the Supreme Court in Alice provided no guidance as to how lower courts are to determine what constitutes an “abstract idea.” In the absence of such guidance, many federal courts have summarily concluded that many software patent claims are drawn to abstract ideas under step one of the test, and are not saved by the analysis under step two. Many software patents have therefore been invalidated as being drawn to patent-ineligible subject matter under Section 101.

Writing for a unanimous panel, Judge Todd Hughes distinguished the Enfish patents from many prior Section 101 decisions under Alice, and provided much needed guidance with regard to the application of step one of the two-part test. Of particular interest to the software patent community is the court’s indication that it does not read Alice to broadly hold that all improvements in computer-related technology (including software) are inherently abstract and, therefore, must be considered at step two of the analysis. According to the court, “software can make non-abstract improvements to computer technology just as hardware improvements can, and sometimes the improvements can be accomplished through either route.”

The court also explained that it was important not to construe claims at an excessively high level of abstraction, lest “the exceptions to Section 101 swallow the rule.” That is, the court cautioned against overgeneralizing the interpretation of the claims under step one, as doing so makes all inventions unpatentable because all inventions can be reduced to underlying abstract ideas and principles of nature.

Applying that reasoning, the Enfish court explained that “the first step… asks whether the focus of the claims is on… [a] specific asserted improvement in computer capabilities…” as opposed to an abstract idea in which a computer is “merely invoked as a tool.” Because the claims at issue in the Enfish patents were directed to a self-referential table that provided various improvements to the operation of a computer, the court found that the claims were not drawn to a patent-ineligible abstract concept. This new application of step one of the Alice test is significant, as many prior patent cases involving Section 101 have summarily concluded that software patent claims are drawn to an abstract idea, thus prompting consideration under step two of the test.

Also notable is how the Enfish court distinguished the claims at issue from the circumstances of various other notable patent cases involving Section 101, including Alice. According to the court, the claims in Enfish are drawn to specific improvements in computer “technology,” whereas the claims in various prior Section 101 cases are drawn to the generic application of computer technology to execute known business methods and/or mathematical formulas.

Although the impact of the Enfish decision will be realized in future decisions, practitioners and businesses should take note of the guidance provided by the court with regard to the abstract-idea analysis when preparing and prosecuting patent applications drawn to computer software. Specifically, patent applications and arguments in support of patent eligibility should focus on the impact an invention has on “computer-related technology,” e.g., improvements to the performance/operation of a computer during the execution of a task.

Arguably, all software improves a general purpose computer to the extent that a computer is useless without software. However, not all software improves computer-related technology. Focusing on how an invention improves the latter may help practitioners and businesses fall on the “patent-eligible” side of the analysis provided by the Enfish court.